A Space of One’s Own - 2019

Challenging ideas that one needs to make ‘serious’ art to be taken seriously, Baadilla and Chi’s exhibitions celebrate and center playfulness and joy.

Exhibiting together for the first time, artists Karima Baadilla and Pey Chi have transformed a street-facing shopfront in suburban Footscray into Open Close Gallery, a temporary exhibition space.

Their dual solo exhibitions Shopping List (Baadilla) and Flower Shop (Chi) explore themes related to everyday life, migrant identity, living with chronic illness, and what it means to make art that reclaims spaces both physical and metaphorical.

The staging of the exhibitions in a shopfront turned pop-up-gallery in Footscray instead of an already established gallery space is significant for multiple reasons. It invites audiences to encounter the works in unexpected ways, while also acknowledging the myriads of ways we may encounter art outside the context of traditional galleries.

In doing so, Open Close Gallery recognises the agency in starting one’s own space rather than subscribing to art institutional structures, which too often can tokenise or marginalise the experience of WOC (Women of Colour) artists. As one of the founding directors of The Artist’s Guild, a social enterprise focused on showcasing female artists, Baadilla is no stranger to creating new spaces where few previously existed.

This idea of making, reclaiming and holding space for oneself, both physically and also emotionally, is also reflected in Baadilla and Chi’s approach to art- making and their respective work. Shopping List and Flower Shop are both culminations of the artists’ previous bodies of work and demonstrate their shared goal in experimentation and play.

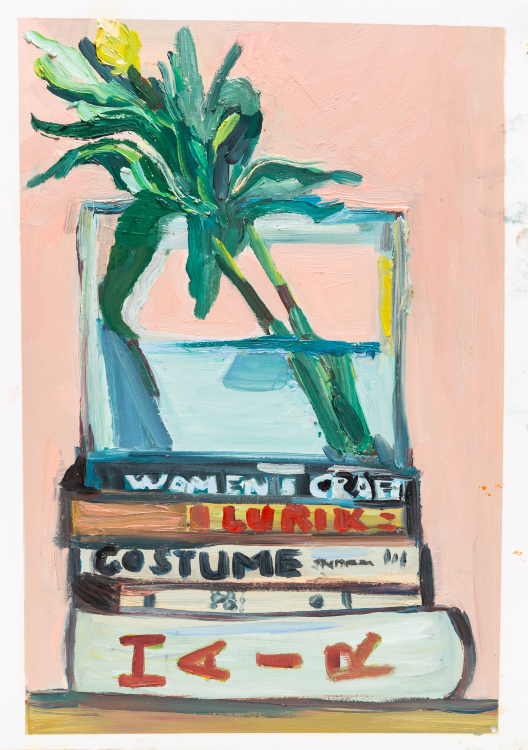

For Baadilla, Shopping List is a return to painting following an extensive period of time focused primarily on ceramics and three-dimensional work. The small paintings range in subject matter from still lives to interiors and self-portraits, but all reveal an introspective approach to subject matter. After the rigour of art school and creating works within that academic context, there is a freedom expressed in Baadilla’s resistance to thematic continuity through this body of work.

From these snippets of the everyday, we gain an intimate insight into the artist’s life and studio. Baadilla works with oils and paints with a sketch-like quality that captures the minutiae of daily life. While there are similarities in style to the legacy of Modernism, it would be limiting to just view these works within this Eurocentric and highly formalistic art historical framework. Baadilla is interested in inserting her own lived experience into her art practice, such as through her choice of subject matter. One common theme across many of the works is a focus on food, particularly foods of cultural significance to Baadilla such as ais cendol (shaved ice drink), kueh onde (green cakes), and condensed milk in order to connect to her Indonesian heritage. The paintings together can be viewed in an almost diaristic manner, which is imbued with the personal narrative and experience of the artist.

The experience of everyday life is also central to the creative practice of Pey Chi, who creates colourful, bright and joyful art as a form of escapism. With a background in textile design, Chi has come to ceramics in recent years as a more freeing medium in which to experiment with different ideas and themes. This in part stems from Chi’s experience of living with chronic illness, and she speaks candidly about her motivations for her practice to ‘express and radiate positivity, a side effect of my chronic illness, that has whole-heartedly changed my life.’ In this regard, the joy that underpins Chi’s works is a positive affirmation not only for the artist, but also a reminder for us all to celebrate the small joys in our lives.

In Flower Shop, Chi has hand-built a number of ceramic flowers, each painted with a face showing either a smile or a frown. This depiction of individual expressions makes each flower unique from the other, as if each has its own distinct personality. Viewed alongside Baadilla’s series of paintings, Chi’s ceramic flowers continue a similar still-life theme but perhaps with more of a nod to an underlying existential question. Still life subjects, particularly picked flowers, have historically been used by artists to symbolise transience and the passage of time by the very nature of their mortality. The depiction of flowers through the medium of ceramics offers an interesting juxtaposition to this idea by capturing these fleeting forms permanently in the form of clay, a material that itself is sourced from the earth in which flowers can grow.

It is in these celebrations of their everyday life and joy that both Baadilla and Chi actively resist and challenge tropes of art-making related to being WOC in Australia. For Baadilla, this is a resistance to the expectations of artists to produce ‘trauma porn’ in order to be taken seriously and that the only way to exist as a WOC artist is to express pain, while for Chi this is a reclamation of ‘cuteness’ as an aesthetic, and recognising how women’s art and labour has been trivialised and policed through these gendered expectations.

Coming together in Shopping List and Flower Shop, Baadilla and Chi have created an exhibition that is about self-assertion, making physical space as a way of taking up space, and holding space for themselves and their community. There is a lot to celebrate here.